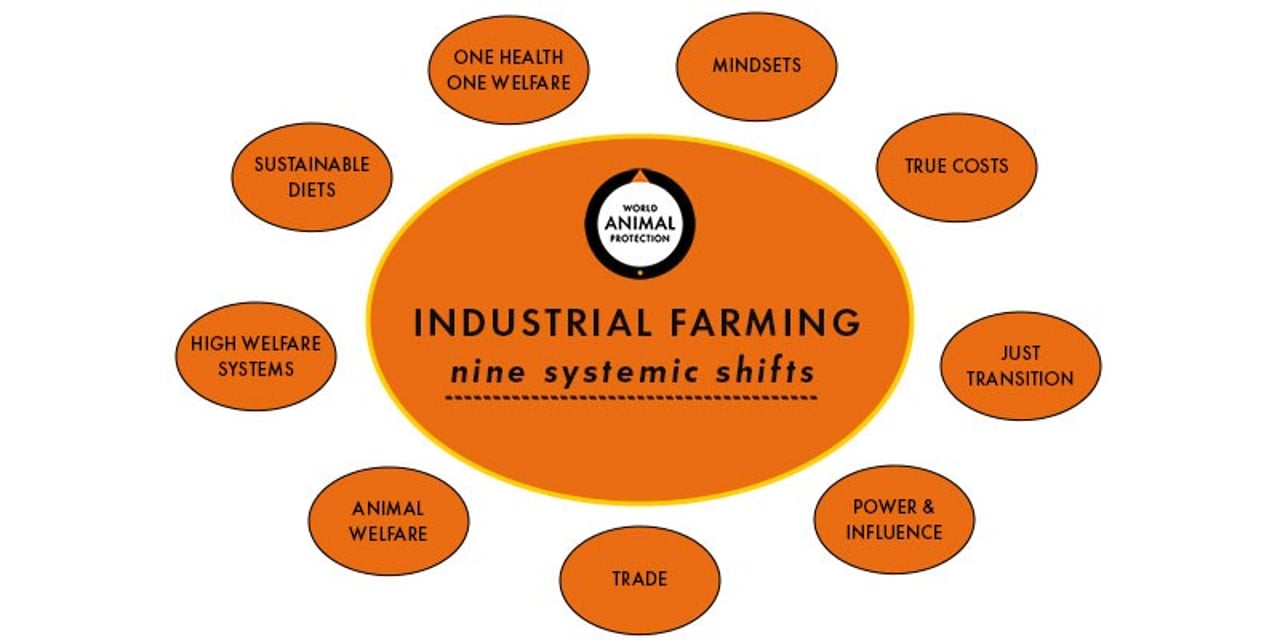

Introducing nine opportunities for better human, planetary and animal health and well-being. Let's explore the big question: Why do mindsets need to shift?

How can we transform our entrenched industrial livestock systems to livestock systems which nourish, restore and regenerate health?

In this blog, we explore nine systemic shifts which have the potential to deliver the biggest gains.

1. A shift in mindsets

2. A shift to true costs and pricing

3. A shift to a just transition

4. A shift in power and influence

5. A shift in trade

6. A shift to higher animal welfare standards

7. A shift to regenerative and agroecological systems

8. A shift to sustainable and healthy diets

9. A shift to One Health, One Welfare

1. A shift in mindsets

Why do mindsets need to shift?

Until we acknowledge that human health, well-being, and happiness are intimately bound up in both our planet’s health and animal welfare, we will continue to be misled by the limited benefits of factory farming methods.

The current mindset focuses on:

- animal food quantity

- calories produced

- financial profit

- maximising economic production

- an export-oriented model

- concentrating food production in a few countries and companies

- the assumption we need more cheap animal products to feed a growing world population

What the current mindset ignores is that industrial livestock systems drive human ill health, animal suffering and environmental destruction.

We need to address the root causes and not the symptoms. This means an end to cruel, unjust, and inhumane and unhealthy factory farming systems with a shift to livestock systems that are humane, healthy, and environmentally sustainable.

2. A shift to true costs and pricing

Many of the broader costs of factory farming are not factored into the industrial livestock business model, where the companies themselves often make massive profits.

For instance, globally we spend an estimated USD 9 trillion on food annually. But here are the real annual costs:

- USD 7 trillion in environmental costs (Health and environment impacts of factory farming)

- USD 11 trillion in human health costs (How industrial farming practices increase human disease risks)

- USD 1 trillion in economic costs

Which means the real costs of factory farming methods are more than double the revenue at some USD 19.8 trillion.1

When these broader costs are factored in, industrial farming practices become more expensive to society as a whole than farming methods using higher animal welfare and environmental standards.

This is why public policy makers need to shift subsidies away from industrial livestock systems to those that support regenerative and agroecological practices.

Articulated semi-trucks transporting soy along the muddy BR 163 road in Mato Grosso Amazon (Credit PARALAXIS / Shutterstock)

There are a range of fiscal tools governments can use, such as taxes and other planning and financial incentives, to reflect the true cost of animal farming. Their aim should be to direct resources towards environmentally supportive, healthy food produced through high animal welfare standards.

Governments can also encourage affordable and accessible healthy and sustainable diets through measure such as social protection programmes or food supplement programmes. These allow governments invest in a wide range of social infrastructure and safety nets, for the wider public interest.

Creating a healthy food environment also supports a dietary shift. Planning policy and urban design for example, play a vital role in shaping these environments and ultimately access to healthy and nutritious foods, such as fresh fruit and vegetables, for the most vulnerable people in society.

3. A shift to a just transition

People and communities need support and planning when moving away from industrial farming practices to high welfare agroecology, regenerative and pastoral systems. This transition needs to work for farmers, farmworkers, abattoir workers, food processors, and disadvantaged citizens.

The support measures needed would include fiscal incentives, practical support, safety nets and social protection. To illustrate the problem, many farmers and workers often feel trapped and that their livelihoods are precarious, squeezed by more powerful players, including large agrochemical suppliers and livestock buyers.

A just transition approach would involve enhancing equity in livestock value chain relationships and ultimately improving the negotiating power of the smaller most vulnerable producers.2

Transition processes should also consider:

- farmers who want to move away from livestock farming into other farming sectors

- opportunities for younger people to enter farming

- cultural sensitivities

- geographic potential

- community rights and decision making

In a recent study, shifting to healthier and more humane and sustainable diets in Latin American and the Caribbean, which reduce meat and dairy consumption while increasing plant-based foods, would create 19 million full-time equivalent jobs despite 4.3 million fewer jobs in livestock, poultry, and dairy sectors.3

4. A shift in power and influence

The governance of industrial livestock systems has changed dramatically over the last 70 years with the liberalization of agricultural markets, the commodification of food and the corporate consolidation of power and influence.

At the same time, those people whose livelihoods, health and wellbeing are most impacted by policy and practice decisions, such as small holder farmers, pastoralists, citizens, processors and packers, seasonal and migrant workers, are often the ones excluded from the decision making process.

In the US, four corporations process 85% of the beef, 71% of the pork and over half of the chicken between them.4 And they create an illusion of choice for the consumer, offering over 60 meat-focused brands between them.5

These corporations are often funded by subsidies from public funds, continues to drive significant hidden external health and sustainability costs, which are picked up by the public purse.

Corporate power and influence pervade the industrial livestock systems with a few companies having a significant influence over government policy making, research, investment, and finance. As a result, the industry has been able to block, undercut and shape laws and regulations that should protect the public from the environmental, public health and economic consequences of industrial livestock systems.6

These corporations also receive significant private sector investment.

Between 2015 and 2020, global meat and dairy companies received over USD 478 billion in backing from 2,500 investment firms, banks, and pension funds around the globe, in the form of loans, underwriting, investment or revolving credit, most of them based in Europe and North America.7

There is an urgent need to shift corporate power and influence which gives the largest livestock corporations unbridled power and influence over the rules that govern our food system and their significant influence in the marketplace.

5. A shift in trade

International trade in animal food products has risen from USD 64 billion in 2000 to USD 173 billion, accounting for 16% of world agri-food trade.8 This trade is dominated by a few large private multinational companies or very large cooperatives, with a heavy bias towards industrially produced animal foods and ultra-processed foods.

Many internal and international trade policies are invariably driven by goals that have little to do with sustainability or health, instead focusing on issues such as economic growth, incomes, jobs, and export earnings. These economic goals in turn tend to reinforce the dominant industrial livestock systems model rather than looking to transform it.

Industrial scale farming practices in many countries has helped to put small- and medium-sized farms out of business, since they are unable to compete economically with large corporations.

This is why there is a need to shift trade policy to reflect the true health, social and environmental costs associated with industrial livestock systems. Without these changes, trade will continue to undermine animal welfare standards and planetary and human health.

One recent report8.5 highlighted the need for policymakers to consider the impacts of trade tariffs on the promotion and importing of ultra-processed foods and reduce the price of nutrient-rich foods, as this can particularly benefit the poorest.

The dumping of foods from European markets (e.g., powdered milk or other animal feeds such as wheat, maize etc.) often undermine prices in local markets9, reinforcing the dominance of global markets in driving health and nutritional standards.

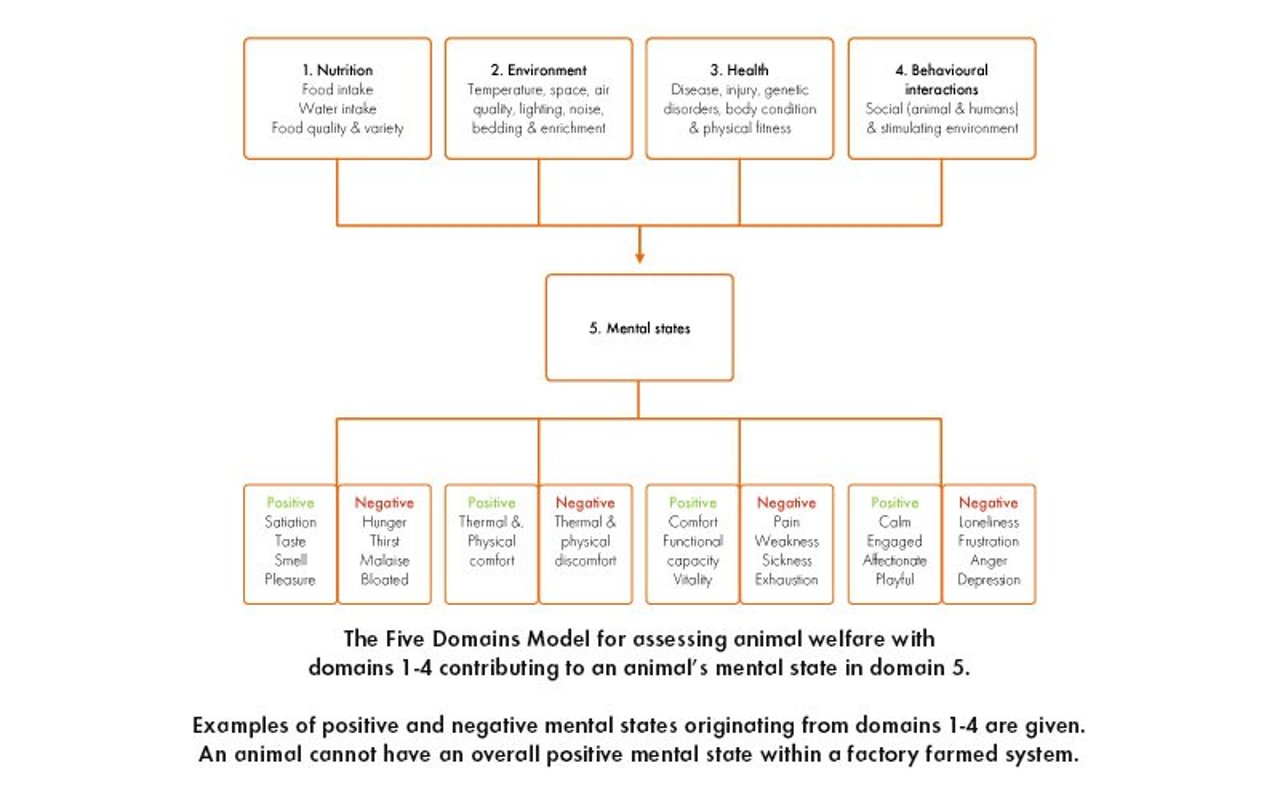

6. A shift to higher animal welfare standards

Many of the human health problems that result from industrial livestock systems could be significantly reduced by adopting high welfare farming systems, where animals are under less stress, develop improved immunity and become resilient to disease.

Which means that there is a need to ensure that all livestock farmers follow minimum standards with respect to how farm animals are raised, transported, and slaughtered.

For example, schemes such as the Farm Animal Responsible Minimum Standards (FARMS)10 outlines minimum welfare standards for existing industrial farms, covering beef cattle, chickens raised for meat (broilers), dairy cattle, laying hens and pigs.

This scheme is designed to eliminate conditions resulting in the worst forms of suffering on factory farms including:

- cages

- confinement

- barren environments

- painful procedures

- extreme genetics

- long distance transport

- inhumane slaughter

These standards can be applied to factory farmed animals, resulting in improved welfare and a life worth living, but don’t necessary mean farm animals will have a good life.

The diagram below illustrates why industrial farming practices can never meet the complex needs of sentient animals.

7. A shift to regenerative and agroecological systems

High welfare agroecological, regenerative, pastoral, and organic livestock farming systems focus on farming practices and principles that can:

- build soil health

- improve biodiversity

- reduce global greenhouse gasses

- improve farmer livelihoods

- improve the nutrition of the poorest

- build health back into the system

They are characterised by farmer owned models and focus on traditional and culturally appropriate breeds of animals which are more resilient to local environmental conditions. In many parts of the world these traditional systems are increasingly being squeezed by more industrial livestock production systems.

Millions of people’s livelihoods depend on these systems as an important source of nutrient rich foods within variable environments where alternatives do not exist. Well-managed silvopastoral systems for example, can increase forage quantity and quality, promote animal welfare, diversify farm income, and reduce pressure on the surrounding forests.11

Redirecting subsidies from industrialised farming systems to agroecology and regenerative practices will bring significant health co-benefits. New incentives to support and reward farmers to transition to higher animal welfare agroecological, diversified practices, and support alternative land use practices and ecosystems integrity, should be a priority for governments.

8. A shift to sustainable and healthy diets

Shifting to healthy and sustainable diets is the single biggest intervention that would help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve biodiversity and the health impacts of our food systems.

Sustainable healthy diets are dietary patterns with the following characteristics:12

- promote all dimensions of individuals’ health and wellbeing

- have low environmental pressure and impact

- improve the welfare of farmed animals

- are accessible, affordable, safe, and equitable

- are culturally acceptable

Several recent studies have demonstrated the significant impact that increasing consumption of plant-based foods relative to animal source foods can have on human health. The EAT-Lancet Commission found that premature mortality could be reduced for up to 11 million people by doubling the consumption of nuts, fruits, vegetables, and legumes and halving red meat and sugars within diets.13

Another study found that 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life years were attributable to dietary risk factors that include high intake of sodium, low intake of wholegrains and low intake of fruits in many countries14.

It is estimated that 80% of all chronic non-communicable diseases are preventable through a combination of physical activity and changes to our diet.15

Where animal based foods are consumed, these should be sourced from high welfare agroecological and regenerative livestock systems, given the heath and sustainability co-benefits these provide as compared to industrial livestock farming systems.

In addition, there is a need to ensure that farmed animals, even under more regenerative and agroecological systems, do not consume food suitable for humans. Farmed animals should only convert food that people cannot consume (grass, by-products, food waste, crop residues etc.), given the inherent inefficiencies and sustainability impacts of converting plant proteins into animal proteins for human consumption.

There is an opportunity for governments to develop national and regional dietary guidelines which should include emphasising the important role plant-based proteins play in meeting the nutritional and cultural needs of local and national populations.

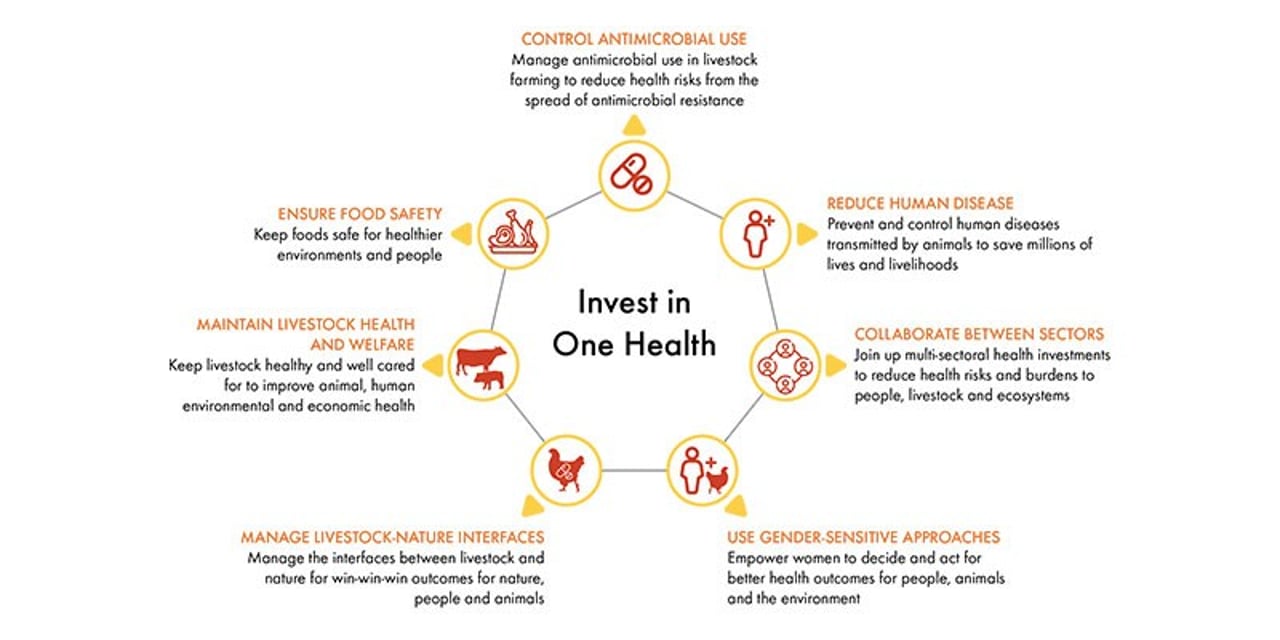

9. A shift to One Health, One Welfare

'One Health' is defined as ‘an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems. It recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and inter-dependent’.16

One Welfare extends and overlaps with the One Health approach and is defined as ‘the interrelationships between animal welfare, human wellbeing and the physical and social environment’.17 A One Welfare approach promotes the direct and indirect links of animal welfare to human welfare and sustainable, humane livestock systems18.

A One Health, One Welfare Approach would enable policy, investment, and research to address multiple health impacts.19

These concepts have gained significant traction in national and international settings and offer an opportunity to mobilize multiple sectors, disciplines, and communities at varying levels of society to collaborate to improve the health and wellbeing of people, planet, and animals.

They demand a shift in policies which focus on treating the disease (a curative approach) to policies that take a systems based approach (preventative approach) focussing on the underlying drivers of ill health across the multiple impact pathways highlighted in this report.

It has been estimated that one dollar invested in One Health approaches can generate five dollars’ worth of benefits at the country level through increased GDP and the individual level.20

To help address these issues, we need to end the growth of factory farming and support a transition to sustainable healthy foods that are good for people, animals and the planet. You can support this process by saying yes to less factory farming.

Say Yes To Less Factory Farming

Read Our Full Hidden Health Risks Report

Make a difference. Join our community.

We campaign to improve animals' lives in the UK and around the world. Why not join us today?

Image credits: Blog listings page: Mark Agnor / Shutterstock; Blog top image: World Animal Protection; business image: Adeolu Eletu/Unsplash; foraging cow image: Anh Nguyen/Unsplash

References

1. UNFSS. 2021. The True Cost and True Price of Food. https://sc-fss2021.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/UNFSS_true_cost_of_fo… (accessed 20th October 2021)

2. Anderson T. 2019 Principles for a Just Transition in Agriculture. Action Aid. https://actionaid.org/sites/default/files/publications/Principles%20for… (accessed 27th October 2021)

3. Saget, Catherine, Vogt-Schilb, Adrien and Luu, Trang. 2020. Jobs in a Net-Zero Emissions Future in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inter- American Development Bank and International Labour Organization, Washington D.C. and Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---rolima/document… (accessed 27th October 2021)

4. Kimberly, K. 2019. This foreign meat company got U.S. tax money. Now it wants to conquer America. The Washington Post (accessed 27th October 2021)

5. Kelloway, C. & Miller, S. 2019. Food and Power: Addressing Monopolization in America’s Food System. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e449c8c3ef68d752f3e70dc/t/614a2… (accessed 8th October 2021)

6. Lazarus, O., McDermid, S. & Jacquet, J. 2021. The climate responsibilities of industrial meat and dairy producers. Climatic Change 165, 30 doi:10.1007/s10584-021-03047-7 ( accessed 30th November 2021)

7. FOE. 2021. Meat Atlas 2021. https://eu.boell.org/en/MeatAtlas?dimension1=ecology (accessed 27th October 2021)

8. V. Chatellier, 2021.Review: International trade in animal products and the place of the European Union: main trends over the last 20 years. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2021.100289 (accessed 28th October 2021)

8.5 GLOPAN. 2020. Rethinking trade policies to support healthier diets. Global-Panel-policy-brief-Rethinking-trade-policies-to-support-healthier-diets.pdf (glopan.org) (accessed 29th October 2021)

9. WHO. 2021. One health high-level expert panel – List of members https://www.euractiv.com/section/development-policy/news/how-eupowdered… (accessed 24th October 2021)

10. WAP. 2021. Fact Sheet Defining humane and sustainable animal protein (accessed 27th October 2021)

11. Chará J., Reyes E., Peri P., Otte J., Arce E., Schneider F. 2019. Silvopastoral Systems and their Contribution to Improved Resource Use and Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from Latin America. FAO, CIPAV and Agri Benchmark, Cali, 60 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. http://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/CA2792EN/ (accessed 25th October 2021)

12. WHO, FAO. 2019. Sustainable healthy diets: guiding principles https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516648 (accessed 25th October 2021)

13. EAT. 2020. Food, Planet Health. https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2019/07/EAT-Lancet_Commission_Summ… (accessed 26th October 2021)

14. GBD. 2019. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8 (accessed 26th October 2021)

15. WHO. 2005. Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment. https://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/contents/en/ (accessed 7th February 2021)

16. WHO, 2017.One Health https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/one-health (accessed 28th October 2021).

17. Rebeca García Pinillos. 2021.One welfare impacts of COVID-19 – A summary of key highlights within the one welfare framework, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, Volume 236, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105262 (accessed 25th October 2021)

18. https://www.onewelfareworld.org/about.html (accessed 25th October 2021)

19. 2021. Livestock pathways to 2030: One Health Briefs 2021. https://whylivestockmatter.org/livestock-pathways-2030-one-health (accessed 15th October 25th October 2021)

20. ILRI. 2021. Joined up investments reduce health risks and burdens to people, livestock, and ecosystems. Livestock pathways to 2030: One Health Brief 1. Nairobi: International Livestock Research Institute https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/113055/OH1_brief.pdf?s… (accessed 28th October 2021)